The Silent Revolution: How Automation Is Transforming Blue-Collar Work Beyond Recognition

In the coming years, blue-collar workers face an unprecedented transformation of their professional landscape - one that defies conventional predictions. This article unveils the complex reality behind automation’s impact on manual labor, revealing why the most widely-held beliefs about this transition are often misleading. You’ll discover: why automation isn’t simply eliminating jobs but radically redefining them, how certain sectors are proving surprisingly resilient to technological displacement, and what adaptive strategies are emerging for both individuals and communities. Along the way, we’ll explore the hidden patterns that determine which jobs face extinction and which will thrive in this new ecosystem. As you journey through these insights, you may find yourself questioning fundamental assumptions about work, technology, and human potential in ways that could reshape your understanding of our economic future.

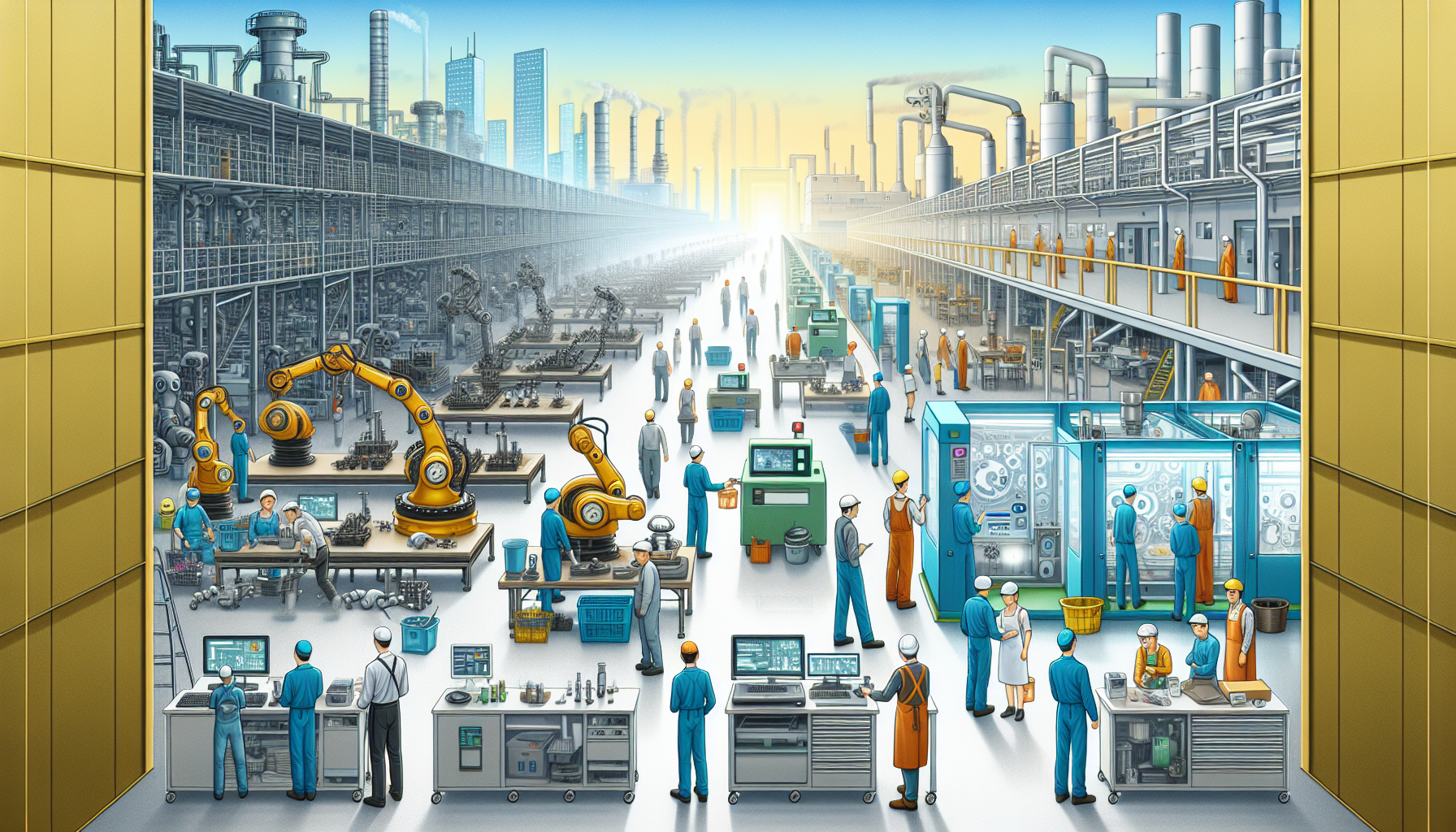

The transformation happening in blue-collar America isn’t merely a technical revolution—it’s a human story unfolding in factories, warehouses, and service industries nationwide. What makes this particular economic shift so fascinating isn’t just its speed, but its selective nature, targeting certain professions while barely touching others. The answers to why this happens, and what it means for millions of workers, contain surprises that challenge our most basic assumptions about technology and human labor.

The Nuanced Reality of Job Displacement

The narrative that automation simply eliminates jobs offers an incomplete picture of a more complex reality. While technological advancement certainly displaces certain positions, it simultaneously creates new opportunities that weren’t previously conceivable.

Consider manufacturing, often portrayed as automation’s primary casualty. Between 2000 and 2010, manufacturing employment decreased by 5.6 million jobs. However, this statistic alone tells only part of the story. During the same period, manufacturing productivity increased by 13% despite employing fewer workers – a development made possible through automation technologies that enhanced efficiency while changing job requirements rather than simply eliminating positions.

The transformation isn’t uniform across all sectors. As economist David Autor notes, “Many middle-skill jobs that are easily automated—such as bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive production tasks—are being eliminated. Yet those that demand a mixture of tasks requiring social interaction, adaptability, and problem-solving skills have proven complementary to technology and are growing in demand.”

This selective pressure creates what labor economists call “job polarization” – the simultaneous growth in high-skill, high-wage jobs and low-skill, low-wage jobs, with a hollowing out of the middle. The result resembles less an employment apocalypse and more an elaborate sorting mechanism, redistributing opportunities based on skill profiles that machines cannot easily replicate.

The Paradox of Construction Work

Construction provides a fascinating case study in automation resistance. Despite significant technological advances, construction has maintained relatively stable employment levels compared to other blue-collar fields. This seeming contradiction stems from several factors that challenge our assumptions about which jobs are vulnerable to automation.

The unpredictable physical environments of construction sites create substantial challenges for robotic systems designed for consistent conditions. As civil engineer James Thompson explains, “Each construction site presents unique variables—weather conditions, terrain variations, unexpected structural issues—that require human judgment and adaptability that machines simply can’t match yet.”

Furthermore, construction encompasses diverse tasks ranging from fine detail work to heavy material handling, often requiring quick transitions between different types of operations. This versatility remains difficult to replicate with specialized machines.

The result? While prefabrication has increased and some repetitive tasks have been automated, the core of construction work remains stubbornly human. The industry has instead seen a shift toward humans using increasingly sophisticated tools rather than being replaced by them—a model of human-machine collaboration rather than substitution that may presage developments in other fields.

The Counterintuitive Vulnerability Factor

When predicting which jobs face automation, we intuitively assume that the most repetitive, physically demanding tasks would be first in line for technological replacement. Reality tells a different story.

Research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology revealed that jobs combining routine physical labor with basic decision-making face greater automation risk than those requiring either pure physical labor or complex decision-making alone. This explains why bank tellers and retail cashiers have seen more displacement than janitors or home health aides.

MIT economist Daron Acemoglu explains this paradox: “The tasks most susceptible to automation are those that follow explicit, codifiable procedures. Many physically demanding jobs actually require situational adaptability and tacit knowledge that’s difficult to program.”

This insight flips conventional wisdom on its head: sometimes, the more physically taxing a job appears, the more it may contain elements of human judgment that protect it from immediate automation. Meanwhile, seemingly secure positions involving routine mental tasks might be more vulnerable than they appear.

The pattern suggests that blue-collar work containing elements of creative problem-solving, interpersonal interaction, or environmental adaptation may prove surprisingly durable in the automated economy. This presents an unexpected opportunity for workers to cultivate skills that complement rather than compete with technological capabilities.

Regional Disparities and Community Impacts

The geography of automation creates stark contrasts between different American communities. Manufacturing-dependent regions in the Midwest and Southeast have experienced disproportionate disruption compared to more diversified economies.

A study by the Brookings Institution found that 25% of employment in Toledo, Ohio faces high automation potential, compared to just 13% in Washington, D.C. These regional disparities create concentrated economic shocks that overwhelm local adaptation mechanisms.

“When automation displaces workers in communities with one dominant industry, the impact isn’t just economic—it’s social and psychological,” notes sociologist Jennifer Carson. “We see increases in substance abuse, family instability, and declining civic engagement that can persist for generations.”

This concentration effect helps explain why national unemployment statistics often mask deeper regional crises. It also highlights why policy approaches treating automation as a uniform national phenomenon often fail to address the intensified impact in specific geographic areas.

Some communities, however, have developed innovative responses. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania transformed from a struggling steel town into a robotics and artificial intelligence hub by leveraging its existing engineering talent and university resources. Greenville, South Carolina pivoted from textile manufacturing to become a center for advanced automotive production.

These success stories share common elements: collaborative planning between industry, education, and government; investments in targeted workforce development; and cultural openness to economic reinvention. They demonstrate that with deliberate preparation, vulnerable communities can navigate technological transition – though not without significant growing pains.

The Skills Transformation Imperative

As automation reshapes job requirements, the critical question becomes: what skills will remain distinctly human in an increasingly mechanized workplace?

Research by the McKinsey Global Institute suggests that physical and basic cognitive skills will see declining demand, while technological expertise, social-emotional capabilities, and higher cognitive functions will become increasingly valuable. This shift creates both challenges and opportunities for traditional blue-collar workers.

“We’re seeing demand growth for what we call ’new-collar’ jobs,” explains workforce development specialist Maria Rodriguez. “These positions combine technical knowledge with human capabilities like problem-solving, communication, and adaptability—skills that weren’t necessarily emphasized in traditional vocational training.”

The transition requires reimagining education systems that have historically separated technical and cognitive skill development. Progressive vocational programs now incorporate both elements, preparing students not just to operate technology but to work alongside it creatively.

Pennsylvania’s Advanced Manufacturing Technical Scholars program exemplifies this approach, combining hands-on technical training with coursework in data analysis, collaborative problem-solving, and systems thinking. Its graduates report 96% employment rates with average starting salaries 40% higher than traditional manufacturing positions.

The model suggests that rather than competing directly against automation, successful workers will position themselves as essential complements to technology—leveraging machines to handle routine aspects while applying uniquely human capabilities to tasks machines cannot perform.

Unexpected Winners in the Automation Age

While certain occupations face decline, others are experiencing surprising growth due to automation’s secondary effects. These “automation-adjacent” jobs reveal how technological change creates opportunities even as it eliminates others.

Industrial maintenance technicians represent one such category. As factories deploy more sophisticated equipment, demand has surged for workers who can troubleshoot, repair, and optimize these systems. Unlike traditional mechanics, these roles require both physical skills and technological literacy—a combination that commands premium wages.

“Ten years ago, a maintenance tech mainly needed mechanical knowledge,” notes industry analyst Robert Chen. “Today’s technicians are part mechanic, part programmer, part data analyst—and they’re earning 30% more than their predecessors while facing virtually zero unemployment.”

Similar patterns appear in logistics, where automated warehouses require specialized operators who understand both physical material handling and digital inventory systems. These positions often pay significantly better than the manual warehouse jobs they replace, though they require different skill sets.

Even in construction, technology-adjacent roles like Building Information Modeling (BIM) specialists have emerged, combining traditional construction knowledge with digital design skills. These workers serve as bridges between physical building processes and the increasingly digital planning systems that guide them.

These examples illustrate a broader trend: automation often eliminates certain tasks while simultaneously increasing the value of complementary human capabilities. Workers who can develop this complementary expertise find themselves not displaced but elevated by technological change.

The Time Horizon Question

The pace of automation implementation presents one of the most challenging forecasting problems. While technological capability advances rapidly, actual workplace deployment often lags significantly behind technical possibility.

Economic analyses reveal several factors creating this implementation gap. First, capital constraints limit how quickly businesses can invest in new equipment. Second, organizational inertia and the costs of retraining existing workers delay adoption. Third, regulatory frameworks and safety considerations often slow deployment in fields involving public interaction.

Labor economist James Milton observes, “There’s often a decade or more between when a technology becomes technically viable and when it achieves widespread implementation. This window creates critical adaptation time for workers and institutions—if they recognize and use it.”

This extended timeline offers an important counterpoint to alarmist predictions of sudden mass unemployment. Historical patterns suggest that while technological change may ultimately transform occupational landscapes, it typically does so gradually enough to allow for workforce adaptation—though this adjustment isn’t always smooth or equitable.

The time horizon also varies substantially across industries. Customer service automation deployed through software updates can spread quickly, while complex physical systems like autonomous vehicles face much longer implementation cycles due to infrastructure requirements, regulatory hurdles, and safety testing.

Understanding these varied timelines helps workers and communities make informed decisions about which adaptations are most urgent and which can be approached more gradually.

Reframing the Narrative: Adaptation Over Resistance

As automation continues reshaping blue-collar work, successful adaptation strategies are emerging at individual, community, and policy levels. These approaches share a common theme: embracing change while ensuring its benefits are broadly shared.

For individuals, continuous skill development represents the most effective protection against displacement. Workers with cross-functional capabilities who understand both technical and interpersonal aspects of their fields consistently show greater career resilience than specialists in narrow technical processes.

At the community level, the most successful transitions involve collaborative planning between industry, educational institutions, and local government. Grand Rapids, Michigan exemplifies this approach, having transformed from a traditional furniture manufacturing center to a hub for medical device production and advanced manufacturing through coordinated workforce development programs.

Policy innovations are also showing promise. Wage insurance programs that temporarily subsidize earnings when workers transition to lower-paying positions help maintain financial stability during retraining periods. Portable benefit systems that aren’t tied to specific employers support worker mobility across changing industries.

“The question isn’t whether automation will transform work—it’s whether we’ll proactively shape that transformation to expand opportunity rather than concentrate it,” argues policy researcher Thomas Gardner. “History shows technological revolutions can either increase inequality or broadly raise living standards, depending on the social choices we make alongside technical ones.”

This perspective suggests that the future of blue-collar work will be determined not just by technological capabilities but by collective decisions about education, economic inclusion, and the value we place on different types of labor. The choices made in the coming years will shape whether automation serves as a tool for broader prosperity or deeper division.

Conclusion: The Human Element in an Automated Future

The transformation of blue-collar work represents not the end of human labor but its evolution into forms we’re still discover:ing. As we’ve seen throughout this exploration, the relationship between technology and work defies simple narratives of replacement or enhancement.

The most successful adaptations will likely come from those who recognize automation not as an opponent but as a collaborator with distinct strengths and limitations. By developing capabilities that complement rather than compete with technological capabilities, workers can position themselves at the valuable intersection of human judgment and machine efficiency.

Communities that thrive will be those that invest in broad-based skill development while maintaining the social cohesion needed to weather economic transitions. This requires looking beyond simplistic job creation metrics to consider the quality, accessibility, and sustainability of emerging opportunities.

As we navigate this complex transition, perhaps the most important insight is that technological change doesn’t happen to us—it happens through us, shaped by our priorities, values, and collective choices. The future of blue-collar work remains unwritten, awaiting the creativity and commitment of those who recognize automation as a tool to be directed rather than a force to be feared.

If you’ve enjoyed this article it would be a huge help if you would share it with a friend or two. Alternatively you can support works like this by buying me a Coffee